As the world works towards COVID-19 relief, new subvariants of the omicron variant are causing a rise in cases, with mutations increasing the virus’ infectiousness.

BA.5 is a subvariant of omicron. In July, it became the dominant strain in U.S. cases.1 Due to mutations in BA.5’s genetic strain, it can evade current vaccines and temporary immunity after a person was recently infected with COVID-19. Its rapid spread has some wondering if it’ll cause a “reinfection wave.”2

Hospitalizations and positive cases are higher throughout the U.S., according to The Hartford’s Chief Medical Officer Dr. Adam L. Seidner. He added that the positivity rate is likely higher than reported “because of unreported tests and individuals not testing.”

At the same time, researchers are also monitoring another subvariant, BA.2.75, to determine if it will become a dominant strain in the future.

“We’re in a cycle of endemic and epidemic periods in the U.S.,” Seidner said. “We’ll likely see a new variant in the future and a significant increase in cases in the fall.”

The recent news of BA.5 can make people worry. How long will the COVID-19 virus mutate? And if it continues, will a new variant or subvariant cause more infections and severe illness?

Despite the increase in cases from BA.5, Seidner said he believes the U.S. will go from a pandemic to an endemic, punctuated by epidemic phases. He added that COVID-19 will be something the world has to live with – much like the flu.

“We’ll have seasonality, where if you’re in closer quarters and inside more, you’ll see more cases of it,” Seidner explained. “So, cases will increase in winter months, but taper off in the warmer seasons.”

Why Do Viruses Mutate?

Mutations occur as viruses replicate within a human or host. It’s a process that happens as part of natural selection, according to Dr. Lisa Chirch, associate professor of medicine and fellowship director for Infectious Diseases at UCONN Health. Chirch explained that viruses mutate to survive, so they may evolve in ways that make them more difficult to detect, prevent or treat.

“Some mutations occur randomly, but others are advantageous from a survival standpoint,” she explained. “These are typically the more dangerous mutations that allow the virus to spread more easily within a community.”

Errors in the replication process cause mutations. A mutated virus is also known as a variant. You can think of variants as strains that are different in some ways, but similar to the original strain.

These changes can have an impact on how severe an illness might be or how infectious the strain is. The human body’s immune system uses the antigens on the surface of a virus to identify it. If there are mutations in the viral strain, it makes it harder for the immune system to identify and fight it.

How Do New Variants of COVID-19 Occur?

New variants of COVID-19 occur as the coronavirus strain mutates within a person’s body. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, variants are expected.3 The global health community has also gotten very good at genomic tracking. So, it’s not unlikely that new variants will be discovered, Chirch added.

“If we look, we’re going to find them,” she noted. “So, we have to be thoughtful and careful in how we consider new variants and their potential impact.”

Although many variants may emerge, not all will warrant monitoring from the World Health Organization (WHO) for causing severe illness or having increased transmissibility. The WHO monitors variants and labels certain isolates as:

- Variants of Concern (VOCs)

- Variants of Interest (VOIs)

- Variants Under Monitoring (VUMs)

As of Aug. 30, 2022, the WHO considers the omicron variant a VOC.

The organization also began tracking subvariants to determine if they pose a threat to global public health. It tracks subvariants under the “VOC lineages under monitoring” (VOC-LUM) category. As of Aug. 30, 2022, there are four VOC-LUMs:

- BA.5

- BA.4

- BA.2.12.1

- BA.2.75

A Look at the Omicron Variant

The omicron variant has at least 50 mutations from the initial SARS-CoV-2 strain.4 Most of these mutations are in the protein spike of the virus, which affects its transmissibility.5 It’s the reason why the omicron variant is so contagious. Because of these differences, it makes it harder for a person’s antibodies to identify and fight the virus. This leads to more infections and even re-infection.

BA.4, BA.5 and Other Omicron Subvariants

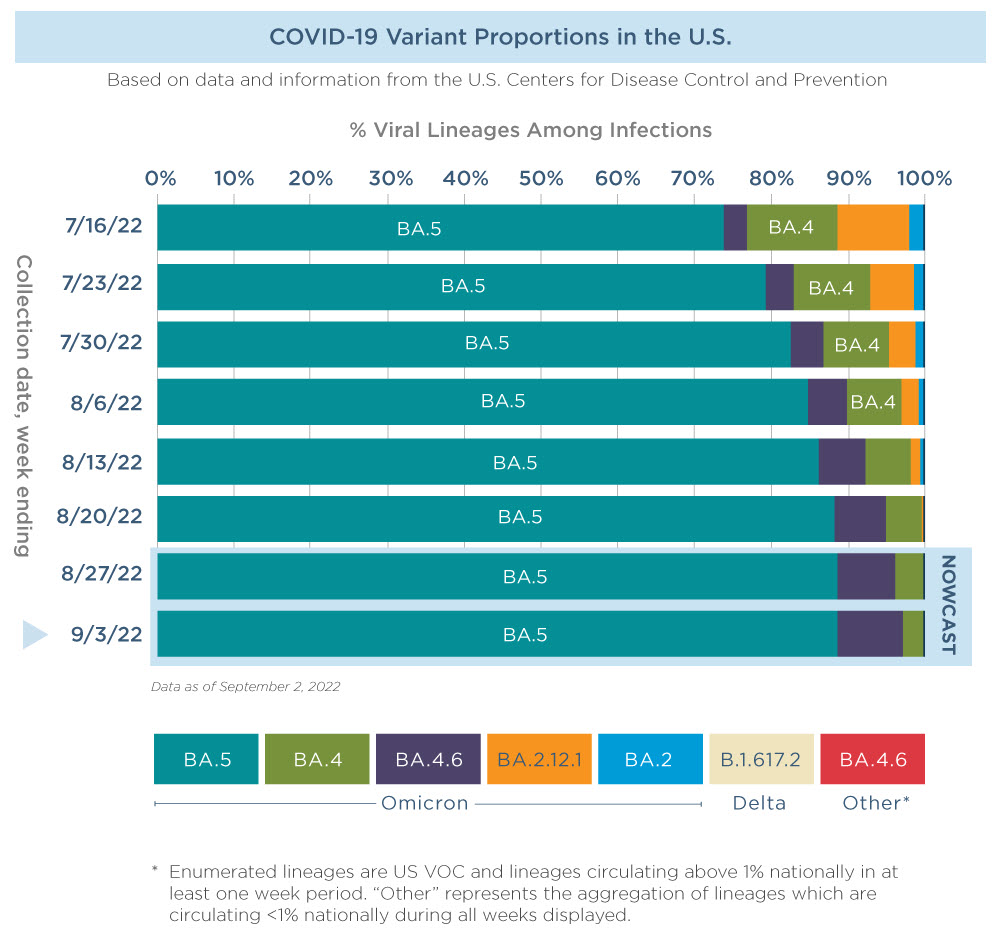

The BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants are spreading rapidly. First detected in South Africa, the subvariants are the cause of recent spikes in cases and hospitalizations. BA.5 is responsible for more than half of all COVID infections in the U.S.

Researchers believe BA.5 is spreading so quickly because of its ability to get past a host’s immune system – even if they have antibodies from a previous infection or are vaccinated and boosted.6

COVID-19 and Viral Shedding

Viral shedding refers to the process of a person infected with a viral infection spreading particles. How long a person sheds the COVID-19 virus remains a relevant question to this day. The answer seems to depend on the variant.

Early in the pandemic, a study showed people spread “high amounts” of the virus early in their infection.7 The same study found that people with mild symptoms were no longer infectious 10 days after their symptoms.8

A recent study in Japan, however, found people infected with the omicron variant shed the virus for longer after exhibiting symptoms.9

R-Naught (R0) Value of Omicron Variant and Subvariants

When trying to determine how quickly an infection can spread in an outbreak, researchers use its reproduction number. Also known as R-naught (R0), it shows the average number of people that one infected person can pass the illness to.

The flu has a R0 of 1. So, an infected person would get one other person sick.

Each surge has been secondary to a variant of COVID-19 that is more contagious as the R0 has increased, Seidner said.

The original strain of COVID-19 had a R0 value of 2 and the Alpha, or U.K., variant had a R0 of about 2 to 3.10 The delta variant had a R0 value of 5.11 One source has the omicron variant’s R0 value as 9.12

Early estimates of the R0 value of BA.4 and BA.5 is 18.6 – double the value of the original omicron variant and about six-times higher than the original SARS-CoV-2 strain.13

Do Vaccines Help Protect Against COVID-19 Variants?

Both Seidner and Chirch said vaccines can protect people from getting a severe illness from COVID-19 and lower the risk of spreading infection.

“If an unvaccinated person gets sick, they’ll have a higher viral load and have a greater possibility of infecting more people,” Seidner explained. “When you’re vaccinated, it means you have less virus shedding. All in all, you’ll be less of a public risk hazard.”

Chirch added that it’s not just the person getting vaccinated who’s protected, but also the people around them who may not have been able to get the vaccine. When talking with her patients about the vaccine, Chirch said she’s honest about her perspective and explains the risks versus benefits.

“I tell them what I think, what my experience has been and why I think it’s the right thing to do – not just for my patient, but also for anybody that they care about,” she explained. “There will likely be people around them that are at higher risk, like small children who can’t yet get vaccinated or loved ones who are immunocompromised. It’s not just about you. It’s about them, too.”

‘Universal Source Control’ To Help Employers Protect Against Viral Outbreaks

The pandemic will eventually reach an endemic stage where COVID-19 doesn’t fully go away. It’ll be something the world will have to deal with on a regular basis – similar to the flu, according to Seidner. Because of this, he believes employers need to take general precautious to protect workers and keep them safe. It’s a principle that he calls “universals source control.”

“You treat everyone as a potential source and you have policies and procedures in place that address that,” Seidner explained. “If you’re sick, don’t come to work. Employers may need to implement other measures, like physical barriers, masking, social distancing, screening and testing.”

In addition, Seidner emphasized the importance of maintaining the HVAC system along with cleaning and sanitization in the office.

1 The New York Times, “As An Omicron Subvariant Spreads, The White House Warns That COVID Is Not Over”

2, 6 The Atlantic, “Is BA.5 The ‘Reinfection Wave’?”

3 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Variants of the Virus”

4 American Society for Microbiology, “How Ominous Is the Omicron Variant (B.1.1.529)?”

5 UC Davis Health, “Omicron Variant: What We Know So Far About This COVID-19 Strain”

7,8 STAT, “People ‘Shed’ High Levels of Coronavirus, Study Finds, But Most Are Likely Not Infectious After Recovery Begins”

9 The BMJ, “COVID-19: Peak of Viral Shedding Is Later With Omicron Variant, Japanese Data Suggests”

10,11 National Library of Medicine, “The Reproductive Number of the Delta Variant of SARS-CoV-2 Is Far Higher Compared to the Ancestral SARS-CoV-2 Virus”

12 National Library of Medicine, “The Effective Reproductive Number of the Omicron Variant of SARS-CoV-2 Is Several Times Relative to Delta”

13 Fortune, “Move Over, Measles: Dominant Omicron Subvariants BA.4 and BA.5 Could Be the Most infectious Viruses Known to Man”

The information provided in these materials is intended to be general and advisory in nature. It shall not be considered legal advice. The Hartford does not warrant that the implementation of any view or recommendation contained herein will: (i) result in the elimination of any unsafe conditions at your business locations or with respect to your business operations; or (ii) will be an appropriate legal or business practice. The Hartford assumes no responsibility for the control or correction of hazards or legal compliance with respect to your business practices, and the views and recommendations contained herein shall not constitute our undertaking, on your behalf or for the benefit of others, to determine or warrant that your business premises, locations or operations are safe or healthful, or are in compliance with any law, rule or regulation. Readers seeking to resolve specific safety, legal or business issues or concerns related to the information provided in these materials should consult their safety consultant, attorney or business advisors. All information and representations herein are as of August 2022.